As far as Nature journals methods go, field notes is probably the method most likely to not meet our expectations. Generally because, our expectations become unreasonable. We expect to have beautiful, colorful, crisp, clean drawings and painting. We expect to magically know the names and fascinating biofacts about all we encounter. We imagine sitting in the bright sun will inspire magnificent poetry and prose and suddenly everyone’s handwriting will be perfect.

In reality, we often end up with kids who are too tired after a day of exploring to put pen to paper, let alone compose and write beautifully. Or, we have one kid who wants to draw the tree over here and another kid who insists on drawing the stream (on the other side of the park). And since your drawing outside, most likely someone dropped their notebook in the mud or the butterfly fly away leaving the artist without a reference.

But I think if we change our expectations, and maybe make field notes just one of many tools in our nature journal toolbox, we can find success in this poorly understood journal method.

The first thing to come to grips with is that field notes are not meant to be a work of art. They are going to be messy, you will probably have a limited pallet of color, and not know what everything you see is. The illustrations will most likely be small, roughly drawn sketches– either because you (and your kids) are on the move, or because whatever you are attempting to draw is on the move. When I teach my Nature Journaling class, I have participates examine some excerpts from the journals of the likes of Lewis and Clark, and Leonardo DeVinci, and Audubon. They always comment on how these famous naturalists and artists field note drawing are, well to be honest, kind of ugly! And then I point out that the purpose of the artists beautiful painting is different then the purpose of their field notes.

So, what is the purpose of the field notes? I’m so glad you asked! The purpose of field notes is to think on paper. To ASK QUESTIONS about all you see outside. Sometimes these will be questions you can answer yourself right away, sometimes these will be questions that require a little research and seeking out help from experts, sometimes they will be questions that require you to observe again and again, and other times they will be questions you choose to leave as questions. Sometime, asking the question is enough.

Here are some examples of questions you might ask in your field notes:

Who? Who (or What animals) did I see and recognize today?

How? How is this animal or plant different from another animal or plant?

What? What was the animal doing? What did I experience/ do on this walk?

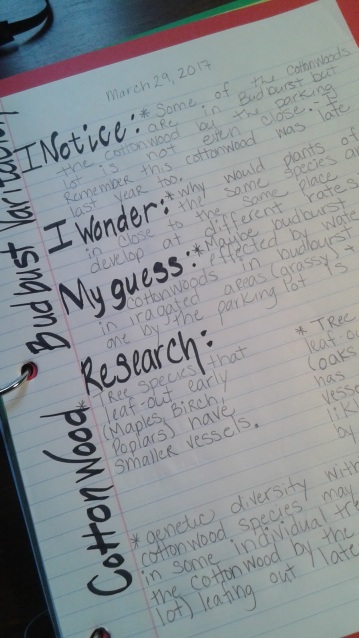

And the granddaddy of all Field Note questions: ” I notice……I wonder……I guess…”

The “I notice, I wonder, I guess” question is a high order thinking type question. It is not one that you can force, and it won’t happen on every nature walk. But when it does happen, you have hit the jack-pot.

This becomes the basis for real learning; information that sticks around and becomes your own personal knowledge.

Some examples of “I notice / I wonder/ I guess” journal entries for my family’s nature journals this past year include:

Example 1: I notice that the leaves change color in the fall and usually the leaves at the top of the tree change first, (and I’ve been told it’s because they loose their chlorophyll), but I wonder where the chlorophyll goes and without the chlorophyll how does the tree have enough energy to make new chlorophyll? My guess is that the chlorophyll travels down the leaves into the tree’s truck where it is stored through the winter and then pushes out into the leaves again in the spring.

**** For the record, my son’s guess wasn’t quiet right. It has more to do this stored energy in the tree’s sap and the constant regeneration of chlorophyll throughout the summer (but not in the fall). But having asked the question, thought about possible answers and then researched the science, the knowledge becomes his to keep.

Example 2: I notice that the Cottonwood tree in the grass, by the street is in budburst, but the cottonwood in the weeds, by the canal is no where near budburst. I wonder why there are variations? My guess is that it has to do with the fact that the tree in the manicured grass gets watered and the tree in the weeds doesn’t.

****And again, my answer wasn’t right at all! Turns out that it is more likely to be genetic variation in the individual trees that cause the difference. Tree species that are native to places with a greater variation in the timing of the last snowstorm, have plants with more variation in the timing of budburst and leaf out.

Now that we know what your field notes are NOT going to look like (works of art) and we know what their purpose is, lets quickly look at what they are going to look like. (Besides crumpled, with some mud smears, and a wrinkled corner from when you accidentally dropped it in the water…)

Here are a few hints for keeping field notes:

-

make sure you include the date (we made this less painful– I’m not sure why my kids found it painful before, but they did– by investing in one of those $7 “library due date” stamps)

-

write the location of where you are (if someone invents a stamp for this I will love you forever!)

-

and make sure to include both simple sketches and writing.

-

Ask and answer some of your own questions.

***Pay attention to your kids and your own “I notice/ I wonder/ my guess” moments****

That’s it. And now as Mrs Frizzle would say:

“Go out there and Take Chances, Make Mistakes,

And Get MESSY”